[published in ArtArtArt magazine, issue 3]

The Armory building during the Whitney Biennial, photo by Jon Meyer - see this Flickr Set for more photos

Park Avenue Armory, New York 6 March – 1 June 2008

Entering the Whitney Biennial 2008 at the Park Avenue Armory, I overheard artist Fritz Haeg speaking to a group sitting on the floor: “I want the piece to be as live and ephemeral and immaterial as possible”. He was referring to his upcoming ‘Animal Drills’, a performance in the drill hall, with dancers performing animalistic movements.

Haeg’s dismissal of materiality is a theme repeated throughout the Armory portion of the Biennial. Indeed, material gestures were so sparse I was surprised when I encountered a room upstairs containing a large cloth tent, sewing machine, large flag bearing a red cross, bars of wax, and army cot beds. Could this be a remake of some Joseph Beuys myth? The thrumming synth background music says not. For ‘Triage’ (2008), DJ Olive intended the beds as places to relax while listening to music. During my stay, one art viewer took up the invitation, collapsing on a bed and closing his eyes. His action illustrated that the beds are not material symbols or mythical sculptural forms. Instead, the message is: kick back, take the weight off, enjoy.

For his piece ‘In the beginning...’ (2008), Bert Rodriguez created a room within a room. It is a small and well furnished white cube. It looks like a waiting room of sorts: clock; two chairs; coffee table. Set in the Armory, I thought of the intersection between bureaucracy and war, of civil servants at home waiting to hear news from the front. But again the objects served a dual purpose, downplaying their symbolic status: Rodriguez used the space during the event to offer daily talk therapy sessions. Art as therapy.

Ties of Protection and Safekeeping (2008) - MK Guth Collection of the artist; courtesy Elizabeth Leach Gallery, Portland, and Whitney Museum of American Art

Ties of Protection and Safekeeping (2008) - MK Guth Collection of the artist; courtesy Elizabeth Leach Gallery, Portland, and Whitney Museum of American Art

In ‘Ties of Protection and Safekeeping’, MK Guth created one of the most visually arresting installations – a transportative room, filled with braided artificial hairpieces and red felt, reminiscent of Tibetan prayer flags. To assuage any concern we might have for this material investment, Guth asked visitors to help braid the work, and to write answers to the question “What is worth protecting” on the cloth strips. The responses were predictably banal, hardly worth protecting: “Art, peace, psychadelics” wrote one. “Catties are god’s kids” said another.

In ‘Our Hour: Radioff’ (2008) Bozidar Brazda hung a metal chair from the ceiling using cables, upside down. The shiny metal looked out of place in the dusty rooms of the Armory, and again I thought of the military, of waterboarding, torture, being suspended upside down. The sounds from a speaker at the back of the room seemed to reinforce this impression, but the descriptive text focused instead on a microphone placed in the room, apparently to pick up ambient sounds from visitors, challenging the definition of “live” radio. During my visit, the microphone seemed to be off.

So it goes on. Ellen Harvey drew fifteen minute portraits of one hundred visitors, and had the sitters fill out a survey questionnaire - harmless pictures and text. Mario Ybarra showed a collection of Scarface memorabilia, making certain to invite visitors to donate new memorabilia to the collection. Eduardo Sarabia made a beer bar open on certain nights. When the bar is not in use, we are instructed to view it as a sculpture. During my visit, the sculpture was covered in empty plastic bottles, echoes of the previous night’s

consumption.

Unifying all of these works is a common theme – a theme that Nicolas Bourriaud best described in his influential 1996 book Relational Aesthetics. These are artworks meant to be judged not for their material qualities, but according to the inter-human relations

which they represent, produce, or prompt.

However, as Claire Bishop says, in her article Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics (2004), “if relational art produces human relations, then the next logical question to ask is what types of relations are being produced, for whom, and why?” This is a question we are left to ponder at the Armory portion of the Whitney Biennial.

I could not help but notice the few objects unquestionably present for themselves. For example, Garrdar Eide Einarsson’s ‘Black Suit (Sic Semper Tyrannis)’ 2008 is a black suit in a frame. It speaks of uniforms, of wearing black suits on days of mourning. Yet the descriptive text for this work indicates it, too, has a social explanation. It refers to Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, an event that converted Tom Taylor’s play into a densely relational moment.

Still from Silent Film of a Tree Falling in the Forrest (2005-6), Mungo Thomson Courtesy of the artist

Still from Silent Film of a Tree Falling in the Forrest (2005-6), Mungo Thomson Courtesy of the artist

The Grand Machine/Theorola (2002) Jason Rhoades, Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Hauser & Wirth and David Zwirner

The Grand Machine/Theorola (2002) Jason Rhoades, Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Hauser & Wirth and David Zwirner

Throughout my visit, the Armory building continuously asserted itself. At the very back of the hall, tucked away in a room easily missed, was a film loop by Mungo

Thomson, ‘Silent Film of a Tree Falling in the Forest’, (2005-06). The film is slightly sentimental in a way that could easily irritate me in another context. But while watching the trees falling, I glanced out at the empty cavernous Drill Hall. Its wooden floor shows scars of a century of hard use, and I thought about how many trees were felled to make that hall. I experienced a chilling sense of awe, fear and wonder. The Armory is its own testament to the huge material consequences of our very non-ephemeral nature. However, this juxtaposition of the Armory with the anti-material art within it went largely unacknowledged.

Later, I visited the Whitney’s Breuer building on 75th Street, to see the rest of the Whitney Biennial. Here, relational aesthetics are quietly put away. Objects are allowed to speak for themselves again. Jason Rhoades’ ‘The Grand Machine / Theorola’ (2002) is a good example. A chaotic mound of objects, each numbered and labeled. The piece depicts a factory production line gone mad, and I think of the production line surely

needed to reassemble this piece. It is unashamedly lush, excessive. In his installation, we are not invited to participate in some pseudo-democratic process. Quite the opposite. This party has already happened. It’s over. Only a tiny number of people were cool enough to be invited. The rest of us are left, instead, to feast on the visual remains. In ten minutes, I realize I am full.

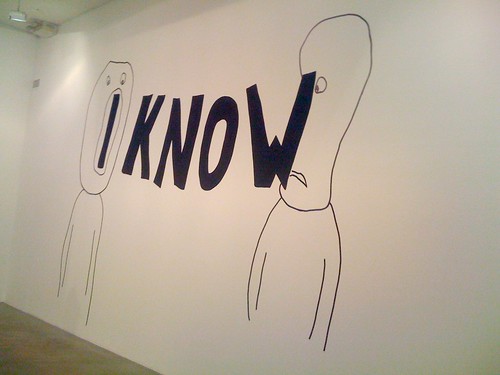

I just visited Olaf Breuning's exhibition at Metro Pictures (519 West 24th street, 11 Oct to 8 November,

I just visited Olaf Breuning's exhibition at Metro Pictures (519 West 24th street, 11 Oct to 8 November,